To Bob or Not To Bob

This was the question throughout the 1920’s. Many women chose to support the bob, despite the disfavor from husbands and fathers. In fact, there were numerous women who didn’t favor the bob. Throughout America, the cultural belief was that long hair was feminine and short hair was masculine. There were also a number of conservative Christians who believed long hair was a sign of godliness in women.

With the passage of the 20th Amendment, women felt freedom to do various activities that they hadn’t engaged in before. For instance, women began drinking, smoking, and driving cars. This reflected their hair as well. It was the singer Mary Castle who said “I consider getting rid of our long hair one of the many little shackles that women have cast aside in their passage to freedom.” More than cutting their hair as an act of celebration, women had a new attitude towards their appearance. Unlike Castle, the actress Mary Pickford didn’t bob her hair. She admitted that though she could make a convincing course about long hair making a woman more feminine, there was some doubt in her mind whether it does or not. Pickford said “Of one thing I am sure: she looks smarter with a bob and smartness rather than beauty seems to be the goal of every woman these days.”

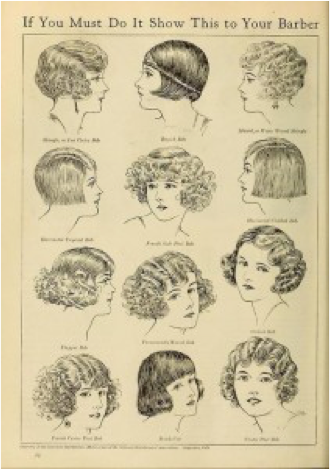

When women discovered their desire to cut their hair, there weren't many salons for bobbing it. Therefore, women went to men’s barbers or tried to cut their own hair. In cities such as New York City, there were reports of up to 2,000 heads per day being clipped. Barbers had to learn how to cut women’s hair, and familiarize themselves with all the latest styles the movies were showing. By the end of the twenties, there were numerous salons across the country. It was too much for women to keep up their hair by themselves. Thus, they took regular trips to the salon.

In order to make it easier for women to keep up their hair, women adopted devices such as the curling iron and large heavy metal rollers. Once women cut their long hair, they realized that their hair was naturally curly but had been weighed down before. There were various styles of bobs during the twenties, including the orchid bob, coconut bob, shingle bob, flapper bob, boyish boy, girlish bob, center part bob, horizontal tapered bob, and horizontal clubbed bob. Bobs with bangs were also common in both curly and straight styles. The actress Billie Dove took her pointed ends of her bangs and did “split curls.” It was widely believed that the number of kiss curls a young woman wore were sometimes thought to be the same number of men she had been kissed by. Moreover, the sculpted waves took on the geometric shapes common in the Art Deco movement− soft at first, angular patterns later. By the late twenties, women began to turn away from curling their hair and instead took the art of Marcel waving. Marcel waving required finger wave sculpting wet hair or a Marcel iron and proved to be quite dangerous if the iron was over heated on the stove. While women were going to a lot of trouble to curl or wave their hair, many African American women were going to the same trouble to straighten their hair.

There were a number of women who didn’t bob their hair. Besides wearing long hair down at the beach, women rarely let their hair hang loose and free. Hair was frequently arranged around the base of the neck or pulled into a bun or chignon at the back. Though the bun had been a working class hairstyle for centuries, the twenties revived it by making it a bit flatter or rolled under for even more smoothness. During the beginning of the twenties, frizzy curls and waves were worn on the side of the face. But in the mid twenties women with long hair wore sculpted waves. In addition, hair covered ears sometimes into flat buns on either side making them look like she was wearing earphones, called cookie garages. In the evenings, long hair was arranged to look like the styles of Greek goddesses. This is because their hair was stacked high, and if a woman didn’t have enough hair of her own, she would add pieces to it by using wads of her own hair, pulled from her own brush.

Prior to the 1920s, women purchased cosmetics at the back door of stores. There was a stigma of women wearing makeup− women who wore makeup were believed to be either pro skirts (prostitutes) or actresses. After World War II, make up was a huge part in helping women recover from the horrors of the war, and assert their new sense of feminine power. Though Gordon Selfridge opened the first cosmetic counter to allow women to ‘try before you buy’ in 1909, it wasn’t until the 1920s that every pharmacy and department store in the world had makeup counters.

The 1920s woman was the first to truly create an artificial face. The defining look was a youthful glow to contrast the ivory pale skin, with creams, powders and various liquids being sold. In addition to loose face powder and liquid rogue, women wore eyeliner, red lipstick and matching lip pencil, mascara, and dark eye shadow. Altogether, the makeup for the everyday woman was much softer and more natural. A number of makeup and beauty books displaying tutorials were at women’s disposal.

Moreover, women applied loose powder to their face. The powder was usually in their skin tone or one shade lighter. Then women applied liquid rouge, also known as blush, to their face. The liquid rogue was mostly red, not pink or orange. Interestingly, women applied rogue to their knees as well.

For their eyes and brows, women applied black or brown pencil. In the very late 20’s, eye pencils came in colors of eye shadow which was an option for evening looks. It was inspired by the huge interest in all things Egyptian, following the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun. Makeup around the eyes was considered too much for the daytime. In fact, only movie stars applied heavy eye shadow. But it was necessary, because they were filming in black and white. Women only applied matte eye shadow heavily once it was evening. The color of eye shadows that women chose to wear frequently matched their eye color. For example, if a woman had blue eyes she should would wear a green or blue eye shadow, with brown mascara and eyeliner. Similar to a substance that the Egyptians wore called kohl, mascara was used in the late 1920s. It came in a cake form that had to be applied with a wet brush. For day time looks, women used brown or black.

In 1923, James Mason Jr. created the swivel lipstick container. It became a staple in every woman’s handbag as well as a matching lip pencil. Both products were usually red. In order to make them look as young and childlike as possible, women over drew the top of their lips. This made what women called a “cupids bow.” It was the actress Clara Bow who made the cupids bow lip popular. With metal lip tracers, shaping the mouth became a major pastime for women. Women tried their best to achieve the perfect pout.

As Kathy Lee Peiss noted in her book Hope in a Jar, “if pale and creamy was the desired skin, the solution for white women lay in array of powders, paints, and bleaches. But what were the ramifications for black women?” The defining look was a youthful glow to contrast the ivory pale skin. African Americans were unable to achieve the defining look. Perhaps they felt as if they were inferior to those who were able to achieve the look. As if reinforcing their sense of inferiority, two of the largest companies within the black community did not sell hair straighteners or bleaches.

There were various makeup brands in the twenties, including Max Factor, Coty, Rubinstein, Arden, Tangee Lipsticks, Peggy Sage, Charles of the Ritz, Bonnie Bell, and Kissproof. Ultimately the most popular makeup brand was Tre-Jur− under the lead of cosmetic entrepreneur Albert Mosheim.

We Just Wanted a Pretty Map

FLAPPER BOB

SHINGLE BOB

ORCHID BOB